From Chapter 3: The Surgical Team

Excerpt

In the surgical team, there are no differences of interest, and differences of judgment are settled by the surgeon unilaterally. These two differences—lack of division of the problem and the superior-subordinate relationship—make it possible for the surgical team to act uno animo. (p. 35)

It's summer; at least for all practical purposes. My attention has drifted north to the trails, cirques and passes of Sierra's. The thought of alpine air and mountain vistas reminds me of the exalting promise I once felt when developing software for space applications before realizing that the actual work takes place behind communication barriers in a bureaucratic miasma. So today, my thoughts have returned to Brooks' Law and the Mythical Man-month.

Brooks has a solution for the communication problem: the "Surgical Team." (See "A fly in the ointment" for a description of the communication problem described by Brooks' Law.)

If you've been reading along, you'll remember there are just two technical contributors on the 10-person "Surgical Team": The "Surgeon and the "Co-pilot." (If not, see "Picking the Archetypes for the Surgical Team".) The Surgeon is the chief. The Co-pilot is #2. The Surgeon's "alter ego." As #2, he or she shares the same responsibilities and skills as the Chief. However #2's responsibility is restricted to that of a sidekick, "thinker discussant" who knows all the code and, maybe even, writes some.

This strikes me as a peculiar arrangement. What exactly is #2 authorized to do on the Surgical Team? In Brooks' scheme: nothing.

For example, what if #2 meanders over to the Editor's cubicle and drops off a few changes to an ICD (i.e. Interface Control Document). Would it be prudent for the Editor to make alterations without being confident they meet the Chief's approval? Hardly.

|

| The co-pilot is only supposed to tap into team communications From Mythical Man-Month p. 38 (1975 version) |

So, in fact, if #2 talks to anyone, his presence probably increases the number of communication paths by N-squared and defeats the very intent of the Surgical Team. That was certainly my experience—I can't recall a time when a reliable decision came out of an audience with a #2.

So, what could reasonably expected from #2?

It's a relevant question for NASA. There is a pandemic of #2's. Typically, they go by names like "Deputy," "Assistant," or "Associate." There are "Deputy Section Managers", "Deputy Architects" and "Assistant Division Managers." That's not to mention "Deputy Division Chiefs", "Assistant Project Managers", "Deputy Directors", and "Associate Administrators". There are even "Deputy Associates" and "Associate Deputies." The list goes on. Any Chief with a scintilla of actual authority is likely to get a #2.

|

| Some chiefs have limited authority |

For example, a chief may get stuck with a #2 whose real job is to guard the interests of a higher authority and ensure the chief steers the party line. Or, he may be stuck with a fallen manager who can no longer land a portfolio and must be parked in a desk job. Or, worse, he may be assigned an-anointed-young-turk who carpools with an executive VP.

On the the other hand, the chief may be a "made man" and have actually authority. In this case he may select his own #2 and use him as he sees fit. Here's a few examples:

Attack dog

Some chiefs have clout

(Meyer Lansky did)

The best defense is a good offense, preferably one that preserves the appearance of impartiality. #2 can keep anyone with an opposing view safely on the defensive. For example, just as a Vice Presidential candidate is expected to relentlessly hector the opposition, a worthy #2 will undercut technical initiatives that threaten the Chief.

Henchman

Every job has its dirty deeds. For example, since the Agency does not tolerate failure (see "Failure is not an option"), remedial measures, like blame displacement, are frequently needed. #2 can do that dirty work so that the Chief's hands remain bloodless.

Parade sweeper

Leadership is not merely a matter of opining with one's feet on the desk — especially in a a paperwork hungry bureaucracy. Someone must take on the stultifying job of feeding the beast meaningless paper. Here's where #2 may make his most meaningful contribution.

Spy

Knowledge is power. A smart Chief must know what the troops are thinking. But, a Chief can have no real friends; unfiltered information seldom penetrates the management bubble. There's too much to be gained by flattery and it's too tempting to rail against leadership. #2 can help. She can be a friend, a trusted advocate for the working stiff, and a reliable reporter of the sentiments that lie beneath the surface.

Hand holder

Two heads is better than one; at least when it comes propping up the boss. With #2 at his side, a Chief makes a much more commanding presence. Best of all the Chief can be assured of close support should he be faced with dissent. There's no better hedge against those unsettling moments of insecurity.

Note to Chief: Effective hand-holding requires occasional dissention to preserve the appearance of honest and considered support. Don't be alarmed.

A short digression

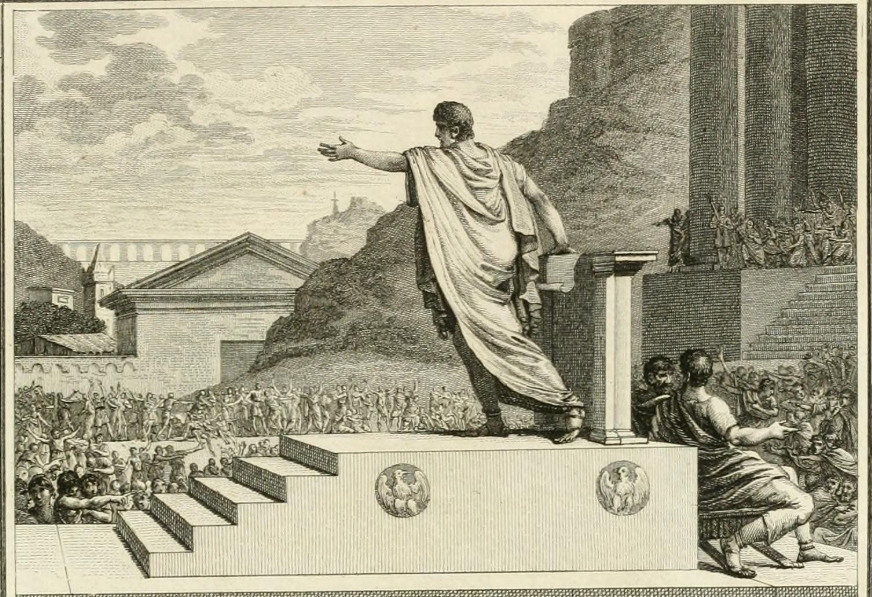

Gaius Gracchus, tribune of the people,

presiding over the Plebeian Council

It was different once. Back in the Roman Republic1 Tribunes2 could only exercise their authority in person.

Tribunes were the elected representatives of the plebeians (i.e. non-aristocrats that held property). They were charged with protecting plebian interests. However, a Tribune was not a magistrate. A Tribune could not create laws, render judicial decisions or have any of the other powers of a government official.

Rather, Tribunes had the peculiar power of being able to veto any magisterial decision, including decisions made by Rome's highest elected official, the Consul. No one could stop a Tribune. But there was a rub. The Tribune had to physically present while the act was occurring. For example if Marius ordered the execution a political opponent, a Tribune could step in and stop the process. But the intervention had to be in person. No deputy. No Associate Administrator. No house guards. No #2 of any label. Only the Tribune's physical presence would do!

In recognition of the threat to life and limb, Tribunes were sacrosanct. Sacrosanctity meant that no one was allowed to touch a Tribune. Any interference was punishable by death. But there was a rub. The minute the tribune left, the act could be completed. The veto had no legally lasting effect.

Imagine how that might change things today.

And then there's the politically motivated selection of #2. This was the case when Napoleon appointed General Jean Victor Marie Moreau to command his Rhine Army.

|

| General Jean Victor Moreau (1763-1813) |

Enter Napoleon. On his return from Egypt in 1799, Napoleon staged a succesful coup d'état that overthrew the Directory.3 Moreau played a key role. As a reward Napoleon named Moreau commander of the Army of the Rhine which lent credibility to Napoleon's fledging reign as First Consul.4

The good feelings would not last. Just months after his receiving his commission, Moreau refused to execute Napoleon's brilliant plan to invade Italy by crossing the Alps.5 Moreau told Napoleon that he should "follow the routes of earlier campaigns." Bad mistake. Napoleon would later write, "It was impossible to overcome the obstinacy of Moreau...He at first refused to command under me...he objected to my plans, pretending that passage of Schaffhausen was dangerous." For the moment, Napoleon did nothing in response to Moreau's insubordination. According to Napoleon, "I was not yet sufficiently firm in my position to come to an open rupture."

Three years later, Napoleon would find the opportunity to dispose of Moreau, but associating him with a Royalist plot. Moreau was forced to flee to the United States, but returned 10 years later to help the Swedes and Russians defeat Napoleon.6

Note to Chief: Don't forget that #2 might reappear as part of antithetical cause. Be nice or be merciless.

| Louis Alexandre Berthier (1753-1815) |

After Napoleon was shipped off to Elba (1814), Berthier retired. When Napoleon returned for the 100 days, Berthier was refused to rejoin the Grande Armee. Two weeks before the Battle of Waterloo, Berthier died by fall from a window.7,8

Note to #2: Your fate may depend on your chief. Enlist with care.

Being #2 is no picnic. For some it's a rite of passage. For others a last resort. But, whether a deputy is motivated by ambition or self preservation, he is not his own master. So observe your #2. Read the tea leaves. There's a lot that can learned about the real politics of your organization. If you aspire to be Chief, your future may depend on it.

Speaking of the future, I see an indigo sky and a few Sierra mountain passes up ahead.

1. The Roman Republic is traditionally dates from ~500-27 BCE when August founded the Empire.

2. Tribune is derived from tribe.

3. Napoleon's coup was a close call that required a good bit of intrigue.

4. In the beginning Napoleon shared power with two other men: Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès and Charles-François Lebrun. Within a year, there was a new constitution that consolidated all power in hands of the First Consul. In 1804, Napoleon would declare himself Emperor.

5. The strategy would lead to the victory at Marengo, one of Napoleon's greatest achievments.

6. He died at the Battle of Dresden.

7. Many historians surmise that Berthier was assassinated. Throwing someone out a window is called Defenestration and is a time honored form of execution.

8. Chandler's "The Campaigns of Napoleon was the source for these anecdotes. Chandler, D. "The Campaigns of Napoleon. The Mind and Method of History's Greatest Soldier." Scribner. 1966. p. 269, 308.